Serve is not Support

A common Organisational Design Mistake

Most organisations have made the same design mistake.

They treat Run as the only work that really matters, Change as episodic disruption, and Serve as a soft layer of coaching, support, and “being helpful”.

That mistake is why organisations externalise unresolved structural load into roles that were never designed, authorised, or resourced to carry it, while mislabelling the result as empowerment.

In the Axion use of Run/Serve/Change

Serve is not support work.

Serve is not coaching.

Serve is not mediation.

Those are behavioural responses to missing structure, not the structural function itself.

In Axion, Serve is the layer that prevents local autonomy from fragmenting the organisation.

When Serve is under-designed, the work does not disappear. It is displaced into roles that were never designed or authorised to carry it, roles without the decision rights, boundaries, or legitimacy required to resolve contradiction structurally.

Some of these roles are filled by people who can temporarily compensate for missing structure. Not because of personality, but because their authority, experience, or cognitive capacity allows them to absorb unresolved contradiction. This is compensatory capability, not design. It scales poorly, transfers badly, and fails silently.

What eventually shows up as burnout, theatre, or “people problems” is not a human shortcoming. It is structural load being carried in the wrong place

In Axion terms, this is Axis 1 load misplacement amplified by Axis 2 ambiguity and sustained by Axis 3 legitimacy avoidance

There is also a less comfortable reason this mistake persists.

Clear structural constraints redistribute power. They remove discretion from individuals and forums that benefit from interpretive authority.

Coaching, mediation, and “being helpful” preserve ambiguity while appearing virtuous. They allow unresolved trade-offs to remain unresolved, decisions to remain reversible, and accountability to remain diffuse.

In that sense, Serve-as-coaching is not just a design error. It is often a political accommodation.

Run (R0): Operational Load

Most people understand Run intuitively.

Run carries operational load:

producing outcomes,

serving customers,

operating services,

Run is where value is realised.

But it is not where all structural loads belong.

Recall that we’re always talking about four different structural loads to absorb.

Operational

Coordination

Integrative

Environmental

When Run is forced to absorb contradiction it cannot resolve; unclear priorities, incompatible rules, unresolved trade-offs, it stops being autonomous and becomes improvisational.

That’s not empowerment. That’s exposure.

Serve (R+1): Coordinative & Integrative Load

Serve is where confusion about “work” really starts.

Serve does not exist to be helpful, supportive, or emotionally intelligent.

Those are failure modes, not functions.

Serve carries coordinative and integrative structural load:

translating Change intent into enforceable constraints,

designing platforms, systems, and grammars that apply across domains,

preventing local autonomy from fragmenting the organisation.

This is integrative work. It is architecture.

When Serve is weak or under-designed, the work does not disappear. It reappears as:

endless cross-team translation,

pre-alignment before decisions,

relational buffering,

escalation theatre.

That is Serve load being absorbed by roles without the authority, mandate, or boundary clarity to resolve it structurally

A coherent Serve layer absorbs that load once, structurally, so Run does not have to absorb it repeatedly, relationally.

Organisations keep getting Serve wrong for three structural reasons:

Run is visible, Serve is invisible, output is celebrated, integration is silent.

Ambiguity preserves power, clarity collapses discretion and forces trade-offs.

Relational fixes are cheaper than redesign, coaching can be added without confronting upstream failure.

None of these are misunderstandings. They are incentives.

And incentives shape architecture as reliably as intent

Change (R+2): Environmental & Integrative Load

Change is often mischaracterised as “strategy” or “vision”.

That misses the real work.

Change carries environmental and integrative load:

interpreting external shifts (market, regulatory, societal),

setting system identity and legitimacy boundaries,

deciding which tensions the organisation will carry and which it will refuse.

This is not planning. It is boundary-setting under uncertainty.

When Change avoids boundary-setting, Serve is forced to integrate against a moving or undefined target. That failure does not stay at R+1, it cascades downward as incoherent constraints and upward as legitimacy drift.

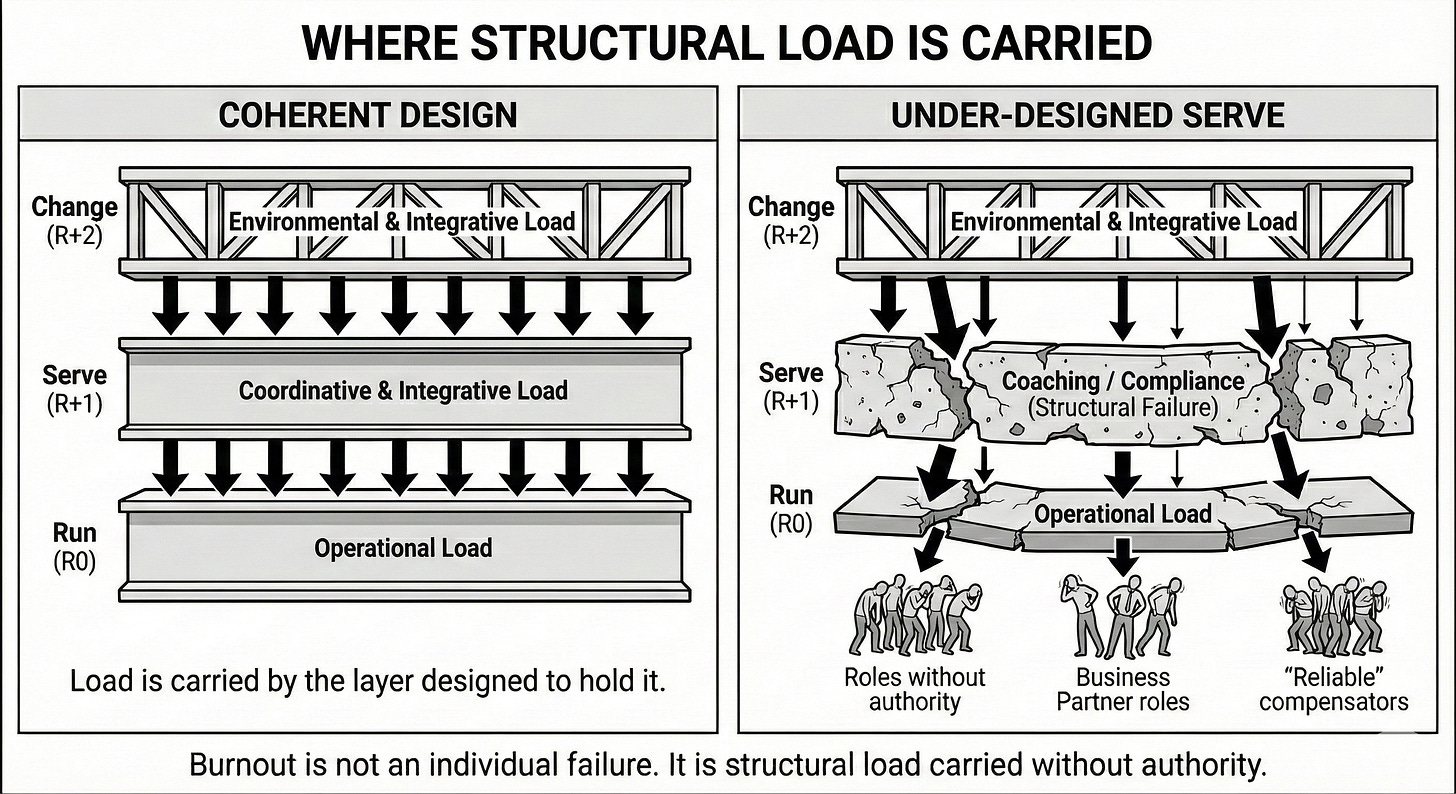

The Pattern Behind Burnout and Theatre

Across organisations, the same pattern repeats:

Change avoids hard boundary decisions

Serve becomes compliance, coaching, or mediation

Run absorbs contradiction through heroics

Everyone is “working very hard”. Very little is held structurally.

This is why saying “Run is the real work” is so dangerous.

It silently licenses the export of structural load onto people.

In Axion terms, this failure pattern is consistent:

Axis 1: structural load is misallocated to roles without authority

Axis 2: regulatory grammar remains implicit or contradictory

Axis 3: legitimacy is preserved through ambiguity rather than design

The Principle

A simple reframe helps:

Run delivers outcomes

Serve prevents fragmentation

Change prevents drift

All three are work. All three are necessary. And each exists so the others don’t have to carry load they cannot resolve.

If you want autonomy without burnout, speed without chaos, and coherence without heroics, the question isn’t how hard people are working.

It’s where the load is being carried.

Example 1: Recruitment (organisation-wide capability)

Recruitment is work and a system. The distinction is not “people vs process”, but where variance is allowed without fragmenting the organisation.

Serve-as-Structure (R+1)

Serve owns recruitment as a coherence problem:

the hiring grammar (what constitutes a valid hire),

risk posture (legal, D&I, security),

platforms and integration (ATS, HRIS, IAM, master data),

non-negotiables embedded in the system.

Outcome:

A constraint-based environment where invalid hires are structurally hard or impossible, without endless approvals, escalation, or heroics to get someone onboard.

Run (R0)

Run designs how recruitment happens within those constraints:

sourcing strategies,

assessment and interview design,

candidate experience,

flow optimisation and local adaptation.

Autonomy is real because the boundaries are real.

If every team invents its own hiring system → fragmentation.

If Serve dictates interview technique → overreach.

Example 2: Customer-facing delivery — Field Maintenance Service

Assume a Responsibility Domain that delivers asset maintenance services (rail, utilities, infrastructure, pick your flavour). Crews perform planned and reactive work in the field.

This is not a “team” problem. It’s a system of work problem.

Serve-as-Structure (R+1)

Serve owns the conditions under which field work is allowed to occur at all, across the organisation:

Work authorisation grammar

what constitutes a valid job,

mandatory safety checks,

escalation thresholds for risk and variance.

Core platforms

work management system,

asset registry and master data,

safety and permit systems,

identity, access, and audit trails.

Non-negotiables embedded in the system

a job cannot be started without required permits,

assets cannot be modified without authorised data updates,

safety-critical steps are structurally enforced, not procedurally suggested.

Serve does not decide how a crew does the work.

Serve makes unsafe, illegitimate, or incoherent work structurally impossible.

Outcome:

A stable operating environment that crews can trust without negotiation.

Run (R0)

Run owns delivery within those constraints:

how crews are organised day to day,

sequencing and batching of jobs,

local problem-solving in the field,

trade decisions within approved risk envelopes,

productivity optimisation (ToC, routing, resourcing).

Crews can adapt freely because the boundaries are clear.

What happens when Serve is weak

If Serve does not carry this integrative load:

supervisors become interpreters of rules,

senior engineers become safety buffers,

experienced staff pre-align and pre-check “just in case,”

escalation becomes the default coordination mechanism.

The work does not disappear. It migrates into roles not designed or authorised to carry it.

That migration is the confusion tax.

Apply the same test

If local variation here is allowed, does the organisation fragment or stay coherent?

Variation in how crews sequence work → safe → Run.

Variation in safety grammar or asset data rules → fragmentation → Serve.

Same logic as recruitment. Different domain.

Why this matters

When customer-facing delivery is treated as the only “real work”:

Serve is redesigned as coaching,

Change is reduced to messaging,

and Run becomes the dumping ground for unresolved contradictions.

Structural coherence isn’t about controlling people.

It’s about deciding where variance is safe and where it isn’t, then building that into the system

Example 3: Nursing Clinical Governance (Healthcare)

Nursing Clinical Governance illustrates why context matters. The same job title can represent either structural integration or compensatory labour, depending on what load it carries.

At first glance, Nursing Clinical Governance looks like an obvious Serve function. In practice, it can be either structural integration or compliance policing, depending on what outcome the role is accountable for (what Responsibility Domain it operates within and at what level of recursion).

Nursing Clinical Governance is Serve (R+1) if:

It is accountable for the clinical nursing grammar at scale (standards of practice, safety thresholds, escalation rules, legitimacy boundaries).

Those standards are designed into systems, not carried by individuals (credentialing rules, rostering constraints, documentation systems, mandatory pathways).

Unsafe or illegitimate practice is structurally difficult or impossible, not merely discouraged.

Ward-level nursing teams (Run / R0) can operate with autonomy because the boundaries are clear, trusted, and non-negotiable.

In this case, Clinical Governance is acting as a Structural Integrator: translating clinical risk, regulation, and legitimacy into constraints that protect Run without constant intervention.

Nursing Clinical Governance is not Serve if:

The work is primarily auditing, inspecting, or reviewing after the fact.

Nurses rely on the individual judgement of the governance role to interpret rules case by case.

Safety is maintained through escalation, exception handling, or personal authority.

The system “works” mainly because experienced people absorb ambiguity and risk.

That is not Serve, it’s human compensation for missing architecture.

A simple diagnostic question:

Are clinical risks prevented by design, or caught by inspection?

Same domain. Same job title. Completely different organisational physics.

This is why Serve gets so easily misunderstood. When Serve is under-designed, integrative and coordinative load is displaced into roles not designed to carry it. The system remains intact by consuming human capacity instead of resolving structure.

Example 4: Business Partners (HR, Finance, Risk, IT)

Business Partner roles are often misunderstood in the same way as Serve.

They are either dismissed as bureaucratic overhead or treated as a symptom of weak design. Both readings are incomplete.

A Business Partner can be a legitimate architectural component.

In many organisations, HR, Finance, Risk, and IT policy landscapes are dense, overlapping, and slow to change. Expecting every Run Responsibility Domain to independently interpret employment law, financial controls, cyber risk, and internal policy would fragment the organisation almost immediately.

In that context, the BP role exists to carry interpretive and coordinative load on behalf of multiple R0 domains.

That is structurally valid.

The problem is not that Business Partners exist.

The problem is what load they are carrying, and why.

Two distinct patterns show up.

Pattern A: BP as intentional structural integrator

The BP role is explicitly designed to:

interpret policy where rules legitimately require judgement,

resolve policy collisions,

translate enterprise constraints into locally actionable guidance,

absorb variance that is uneconomic or unsafe to codify.

Here, the BP is part of Serve by design.

Judgement is intentionally located in a role, with legitimacy and authority to act.

This is not a workaround. It is architecture.

Pattern B: BP as compensatory mediator

The BP role becomes necessary because:

policies contradict each other,

systems are fragmented or overly complex,

decision rights are unclear,

approval paths are implicit rather than designed.

The BP spends most of their time:

explaining “how it really works”,

pre-aligning decisions before formal forums,

shepherding requests through opaque processes,

acting as an escalation buffer.

Here, the BP is still part of the system, but they are compensating for unresolved design debt.

This is where confusion tax accumulates.

The critical distinction is not whether judgement sits in a role, but whether that judgement is carrying intentional load or leaked load.

A simple diagnostic:

If the Business Partner disappeared tomorrow, would the organisation fragment because essential judgement was removed or would it fragment because contradictions were being silently absorbed?

If it’s the first, the role is doing legitimate Serve work.

If it’s the second, the role is signalling where Serve and Change have failed to simplify, integrate, or decide.

Axion does not argue that all such load should be designed away.

It argues that organisations must be explicit about which load they choose to carry through roles, and which load they are unknowingly exporting into people’s working lives.

That distinction is the difference between coherence and quiet exhaustion

The critical contrast

This is the distinction most organisations never make explicit:

1. Serve-as-Structure (what it should be)

Sets constraints, not behaviour

Integrates systems, platforms, grammars

Reduces relational load

Enables autonomy at scale

Failure mode: constraint overload

2. Serve-as-Coaching (common but fragile)

Smooths friction manually

Translates between groups

Relies on trust and goodwill

Masks structural incoherence

Failure mode: emotional exhaustion

3. Serve-as-Compliance (worse)

Polices rules after the fact

Enforces incoherent constraints

Increases friction and delay

Incentivises workarounds

Failure mode: theatre and resentment

If Serve is coaching or compliance, it is already too late.

The system has failed upstream.

The simple test

If this varies locally, does the organisation fragment or remain coherent?

If it fragments → Serve owns the structure.

If it doesn’t → Run owns the design.

This isn’t about centralisation.

It is about where structural load belongs.

Now what?

If you recognise that your Serve layer has collapsed into coaching or compliance, here’s the first diagnostic to run tomorrow

Pick one recurring coordination problem. Trace whether it’s being absorbed by structure (platforms, constraints, automated rules, roles with the requisite authority and mandate) or by people (pre-alignment, informal interpretation, personal authority). If it’s the latter, you’ve found leaked Serve load. That’s where to start.

What you’re really describing here is legitimacy computation drifting away from work-as-done and into interfaces.

Once that happens, Run/Serve/Change stops being a design problem and starts behaving like a coordination artifact: load migrates into people because the system no longer knows where to put it.

From that angle, burnout and theatre aren’t organizational failures so much as equilibrium states in a post-institutional environment.

Curious whether you see this as primarily an organizational pathology or as a local manifestation of a broader shift in how power now organizes itself beyond institutions.

I want to test my thinking here and hopefully provide a useful metaphor. Considering spinning this out into a longer series on the parallels between game design and work design.

So: I have not done large scale OD work. I've never led a change transformation program. However, I have played an absurd number of video games, board games, and roleplaying games.

Games are a helpful metaphor, I think, because they're a microcosm of agency. Game designers are agency designers. An organisational designer can do a subpar job because the purpose of an organisation (or component thereof) provides some basic coherence. This basic coherence, even if it's diffuse and confused, grounds the heroics of 'Run' — treating patients, drilling for oil, or whatever.

A game designer has no such luxury. If the game is not fun (which is to say: if the agencies are unclear) players will simply stop playing. Game designers have to be more selective than organisational designers with structural load. Therefore, games are a model of structural load done right.

So, with that in mind:

- Run (Axis 1) is playing the game. Players have clearly defined agencies and goals, and within the game have end-to-end responsibility over clearly defined domains and outcomes.

- Serve (Axis 2) is the game's rules and goals. These are legible, explicit, and codified. The game designer has to do this well because they cannot be physically present to adjudicate them — any and all insight needs to exist in the box (or in the code, if it's a video game). The rules need to be simple and coherent enough to be enforceable by players without oversight.

- Change (Axis 3) doesn't apply so much here since a game is typically a fixed artefact, but it could be e.g. regionalisation of games (Monopoly Australia), thematic adaptations to reach new markets (a SciFi reskin of a fantasy game), rule adaptations to changing player needs and desires (T20 cricket), or the phenomenon of house rules in games. This could also include what Bernard Suits calls 'ludic attitude,' the perspective players bring to games that gives a game designer moral authority.

The metaphor extends a bit further. Consider Dungeons and Dragons, where the Dungeon Master (DM) functions a bit like a HR Business Partner. The game is sufficiently complex that rules demand some interpretation. The DM exists for both interpretation across rulesets (e.g. adjudicating between preserving the narrative while respecting combat mechanics) and as a carrier of tacit knowledge.

Which perhaps brings me to a question, pulling from the metaphor: Is there a place for tacit knowledge in the 'Serve' layer? Not all boundaries can be fully codified and enforced and some coordination and integration work is always non-propositional in nature.